When selecting a basting method for plaids, consider the complexity of the plaid, the texture of the fabric, and the garment design, as well as your sewing skills. Here are a few basting methods that can help you achieve precise plaid matching:

When selecting a basting method for plaids, consider the complexity of the plaid, the texture of the fabric, and the garment design, as well as your sewing skills. Here are a few basting methods that can help you achieve precise plaid matching:

First Step

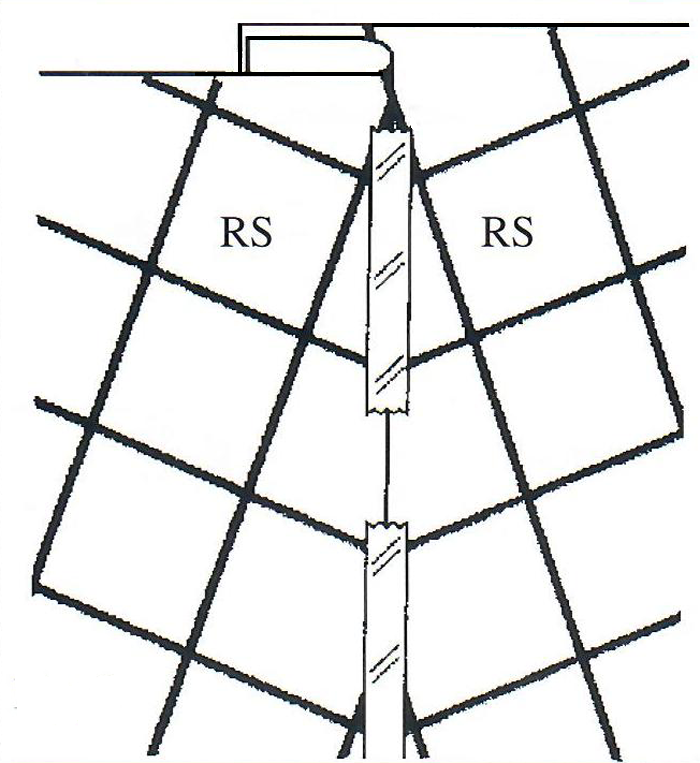

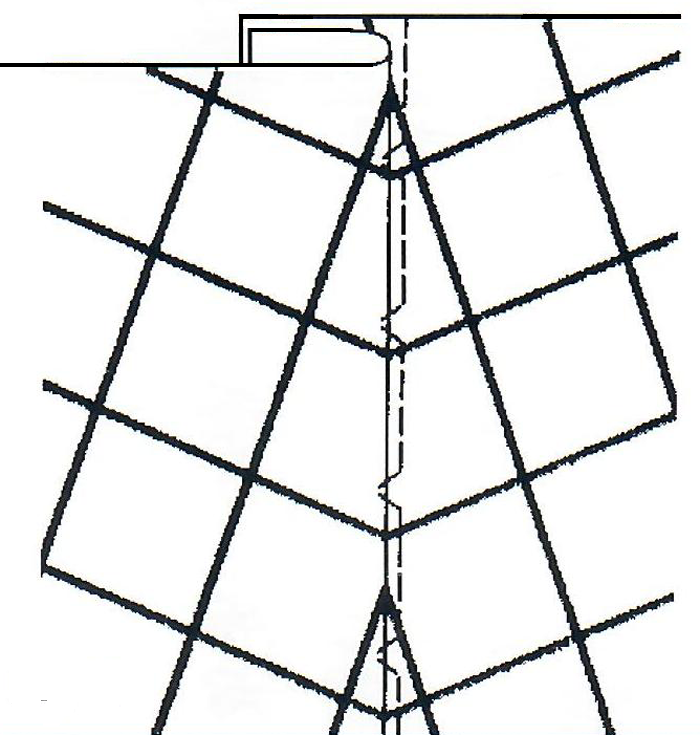

For best results, baste with the right sides up. It’s also helpful to stay stitch the edges of your fabric pieces. This helps maintain the shape of your pieces while you work on matching the plaids.

Glue Sticks and Tapes

Glue sticks and water-soluble double-stick tape are easy basting techniques that could work well on some fabrics where, for example, needle punctures would not be appropriate. Position the glue or tape just inside the seam line on the right side of the unpressed section. Align the plaid bars and press the layers together. Let the glue dry before stitching.

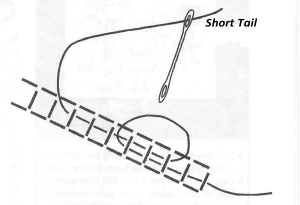

Another easy basting method is to use drafting tape. Match the color bars and tape the sections together. Then, right sides together, stitch from the wrong side on the seam line. (Figure 1).

Tip: Before using drafting tape, test to be sure the tape won’t mar the fabric or pull off the nap.

Hand Basting

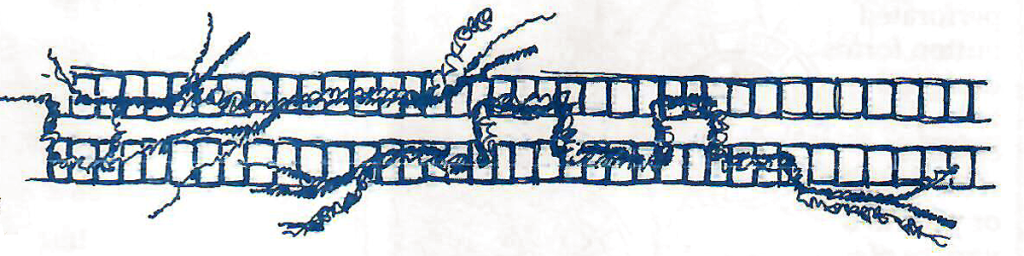

For difficult seams, hand-baste. With right sides up, align and pin the sections together. Then use a short slip stitch or fell stitch to baste. Use a contrasting thread color that’s easily visible against the plaid pattern.

- The fell stitch tends to hold the fabric a little more securely; however, on the wrong side, the stitches are slanted and if you aren’t using a water-soluble thread in the bobbin, they are more difficult to remove.

- If using the slip stitch, consider adding a safety by turning the garment over and putting in a second row of basting from the wrong side so that there are no spaces in between the stitches.

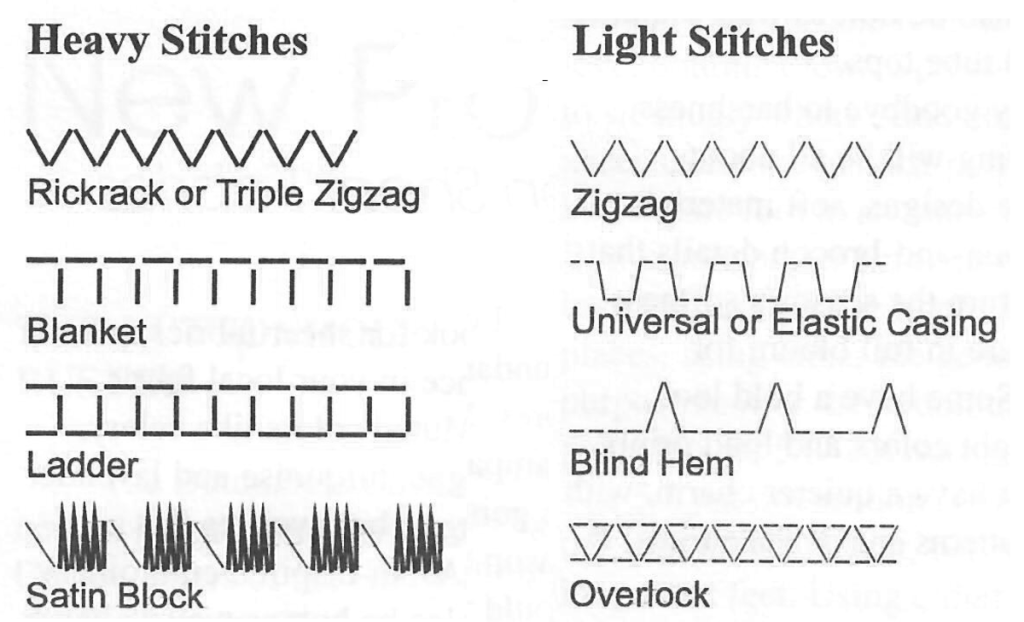

Machine Basting

Machine basting works well on fabric that won’t be damaged by extra needle holes. With right sides up, align the color bars and pin the sections together. Set the machine for a blind hemming stitch (Width: 2″, Length: 2.5″) and a loose tension, then stitch next to the fold line. Only the zig-zag stitch will catch the fold line (Figure 2). Consider using water-soluble basting thread in the bobbin, but remember that this thread could dissolve in hot, moist hands or when wound on to a bobbin at high speed. In this method, it could help to use a contrasting thread color that’s easily visible against the plaid pattern.

Pin Basting

Pin the plaid pattern pieces together along the plaid lines, making sure the lines match up perfectly. Place the pins parallel to the plaid lines and about an inch apart, then place the pins in both vertically and horizontally to keep the pattern pieces aligned.

Clipping and Notching

When you have intersecting seams, clipping into the seam allowances or notching them can help align the plaid lines more accurately. Make small diagonal snips (clips) or triangular notches along the seam allowances, being careful not to cut into the stitching line.

~Partial contribution from an ASG article by Claire Shaeffer