With shifts in the garment and fabric industries which ultimately decreases the range of fabrics available as yardage, resale and thrift stores emerge as a great source of materials for special sewing projects.

It was a contest to make best use of Pantone’s 2024 color of the year – Peach Fuzz – that had me searching through the resale racks for an item that included that color plus some kind of surface interest- shine, drape, texture, or jacquard perhaps. A V-neck pullover sweater combined the perfect color with a purl-stitch surface. A plan immediately took shape – open the center front, add a banded finish, and find some interesting embellishment.

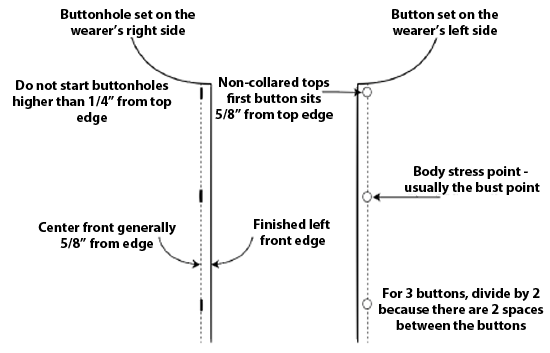

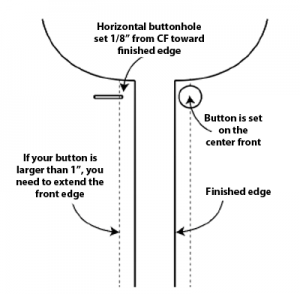

To create the cardigan shape, I reinforced the center front of the sweater (wrong side) with 1/2″ fusible tape on the wrong side, stay-stitched approximately 1/8″ on either side of the center front and split the fabric to create an open edge.

Pamela’s Patterns #108 (New Versatile Twin Set) provided the pattern piece for the front band and facing, modified to fit the existing neckline shape, barely overlap the center front edge, and extend beyond to create a bit of overlap.

To avoid the bulk of enclosed seams, I cut the bands from a color-matched ponte knit (ST Ponte available at NancyNixRice.com) and trimmed away the seam allowances, knowing that the fabric wouldn’t ravel.

The lapped edges of the band pieces were temporarily secured to the sweater with ¼” Double Sided Fusible Stay Tape from Emma Seabrook. (I’m fairly certain I couldn’t sew at all without that product.) The free edges of the outer band and the facing were also fused together, and all the edges were secured in place with a hand-sewn blanket stitch using 3 strands of color-matched embroidery floss.

The matching ponte shell is sewn exactly per the instructions, then finished with the same (slightly imperfect) blanket stitch around the scoop neckline.

So far, so good. But the combo still needed a bit of oomph. Searching my neighborhood Joanne Fabrics for some appropriate embellishment, I hit paydirt: a bolt of ultra-sheer tulle embroidered with pastel floral motifs that included Peach Fuzz!!

Three-eighths yard of that fabric yielded the perfect vines and buds to cut out and hand applique onto the upper bodice of the sweater. By stitching down only the green stems, I could keep the buds and leaves un-secured, for a fully 3-D effect. A sprinkling of blossoms carried the decorative effect onto one cuff and one back shoulder for a truly designer finish.

What treasures-in-the-making are lurking in your local resale outlets? Maybe some inspiration in the 2025 Color of the Year: Mocha Mousse.

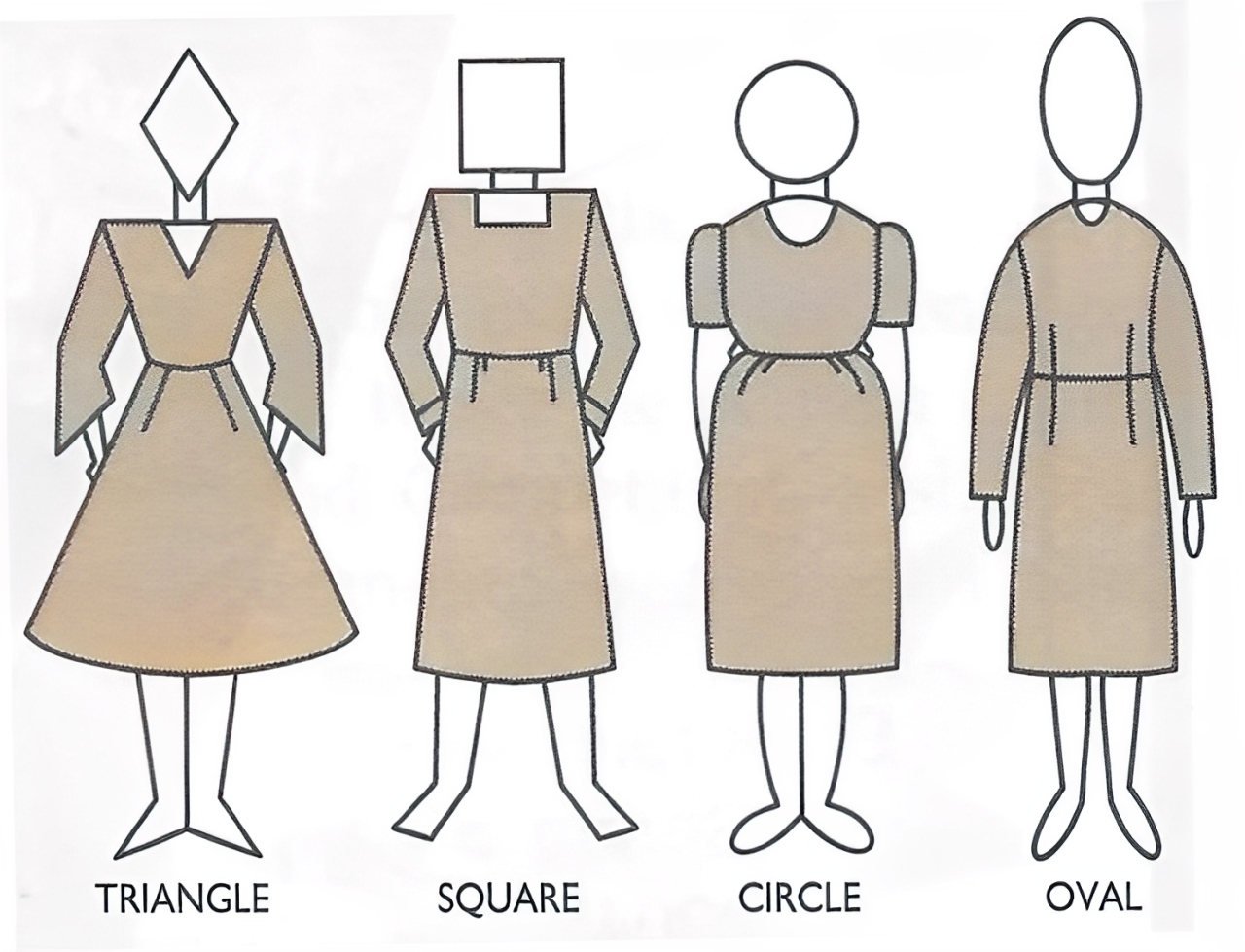

~Nancy Nix-Rice is an image and wardrobe consultant who specializes in helping sewists make optimal wardrobe choices. You can subscribe to her newsletter at https://bit.ly/3SRtPoq