If you’ve made bags, totes or packs, you may have had to deal with a gusset or two.

So, what’s a gusset?

The word gusset doesn’t roll easily off the tongue and may not be something of common knowledge. But the purpose of this design detail is to add depth and more room to a project. Rather than creating a perfectly flat tote, bag or purse with just a back and front, it’s handy to have space for more items inside.

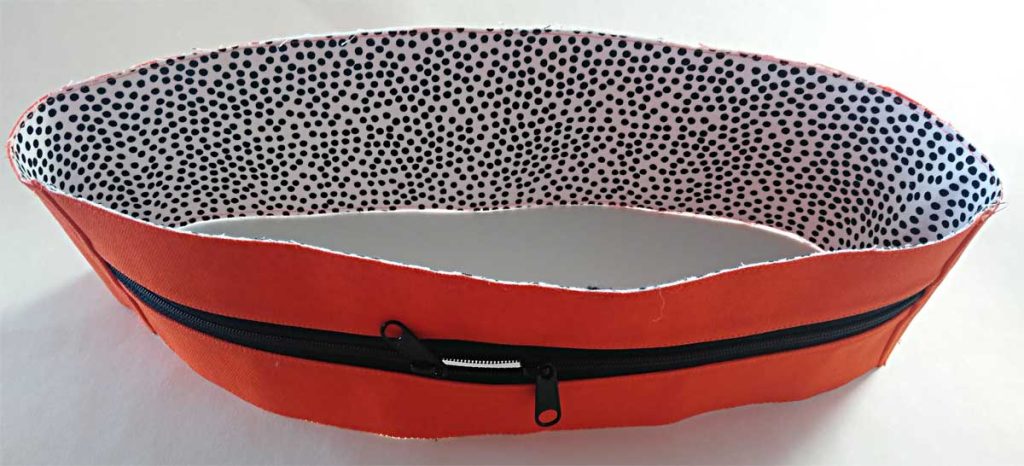

A gusset is basically a strip of fabric that goes fully or partially around a bag for this purpose. Most gussets also feature a zipper opening for access to the interior of the bag. A gusset also allows a bag to stand on its own.

Gussets on Garments: Gussets in garments are pieces of fabric inserted to add width, strength, or comfort. They’re commonly found in areas that need extra ease of movement, such as the underarms of sleeves or the crotch of pants. Sewing gussets into clothing is a different process than adding them to bags or totes.

Gussets can be the same width throughout or can be wider at the bottom tapering to narrow or non-existent by the time they get to the upper bag edge.

Adding a continuous band around a base shape can be tricky—not only are there corners or curves involved, but the gusset has to fit the piece exactly so there are no puckers or gaps, and if the bag has square corners, you don’t want any pleats at the corners.

Piece by Piece

If your bag has a zipper closing, you’ll likely have two upper gusset pieces to cut—one for each side of the zipper. If the bag is lined, there will be four upper gusset pieces—two outer fabric and two lining fabric.

While some gussets are constructed slightly differently, the pattern guidesheet should detail the process, but shown here is the general process for most bag gussets.

To construct a zippered upper gusset, place the zipper tape face down on one gusset with the long edges matching and baste in place close to the edge (1).

If the gusset is lined, place the lining piece right sides together with the gusset and stitch in place along the seam line. Press both gusset layers away from the zipper and topstitch (2).

If the zipper is longer than the gusset, unzip it halfway and sew across the end several times, then trim off to match the gusset length. Repeat for the other end if needed (3).

With right sides together, sew the bottom gusset to the top gusset across the gusset width. This creates a circle which should fit your bag back and front exactly. Press the seam in one direction and topstitch through all layers (4).

Note that if your bag is lined, the lining lower gusset will be part of the seam (5)—check instructions for your specific bag.

Now comes the fun part—attaching the completed gusset to the bag front and back. Pin-mark the top and bottom gusset centers, then fold those marks to match, and mark. This divides the gusset into equal quarters. Create those same sectional markings on the bag back and front (6).

With right sides together, match the quarter markings on the bag with the same on the gusset starting at the top center and clip the layers together (7). If the bag back has rounded corners, slash into the gusset seam allowance only and spread apart to round the corners.

Clip all layers together (8). If the bag has square corners, slash the gusset once and spread at the corner seam. Start along one side and sew the gusset to the bag section around the perimeter, allowing the gusset notches to spread around the corners. No puckers!

With the zipper partially open to allow for turning, repeat the process to attach the remaining gusset side to the remaining section of the bag. Yes, it’s a bit like standing on your head for this step as you’re wrestling the other side and gusset but stay the course and keep an even seam allowance. Turn the project right side out and check for any puckers or pleats. Trim the seam allowance if the pattern directs. Voila—gusset installed!

Complete the project per the pattern instructions.

~Linda Griepentrog is the owner of G Wiz Creative Services and she does writing, editing and designing for companies in the sewing, crafting and quilting industries. In addition, she escorts fabric shopping tours to Hong Kong. She lives at the Oregon Coast with her husband Keith, and three dogs, Yohnuh, Abby, and Lizzie. Contact her at gwizdesigns@aol.com.

We all know that flossing is good for your dental health, but the floss itself can be helpful in your sewing room as well.

We all know that flossing is good for your dental health, but the floss itself can be helpful in your sewing room as well.

Flex straws that bend allow for even more precise placement in awkward areas.

Flex straws that bend allow for even more precise placement in awkward areas.