Perhaps you remember that challenging childhood game of pick-up sticks where you had to carefully remove a stick without disturbing the others around it? Well, that nostalgic game has inspired a fun sewing technique showcasing brightly colored channels inset at various angles onto a base fabric.

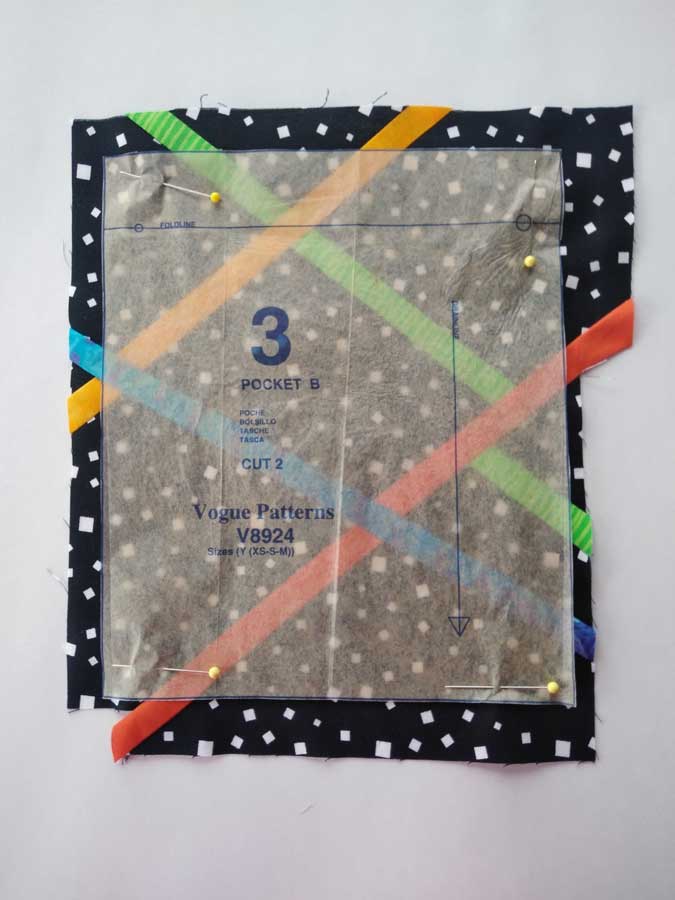

Whether you use this technique to create artistic fabric for a small project, a section of a garment (like a pocket, collar, cuff, etc.), or for a quilt, it’s sure to provide some fun sewing time. For purposes of these instructions, we’ll refer to the larger piece as base fabric.

Tools

Rotary cutter, ruler, and mat

Preparation

- Cut the base fabric 1 ½” – 2” larger than the finished size needed. For example, if you’re making a pieced collar, create a rectangle that much larger than your pattern piece.

- Cut the assorted color inset strips 1” wide.

Cutting Up

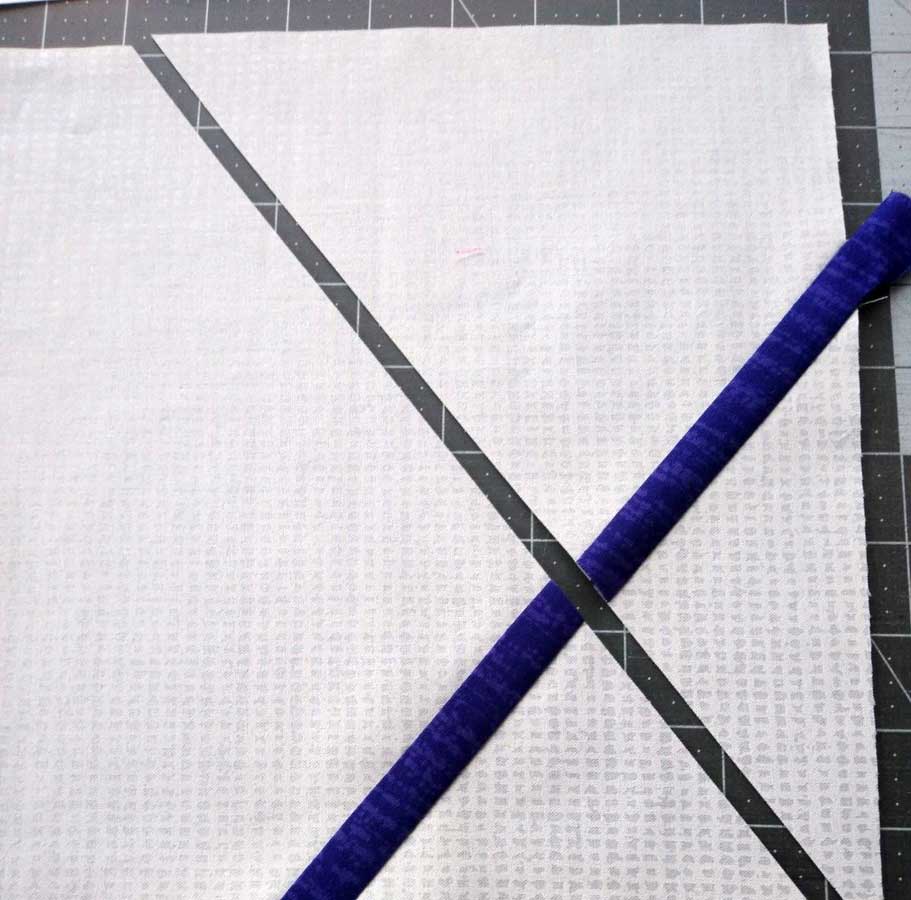

Lay the base fabric right side up and make your first cut at any angle you like, cutting it into two sections.

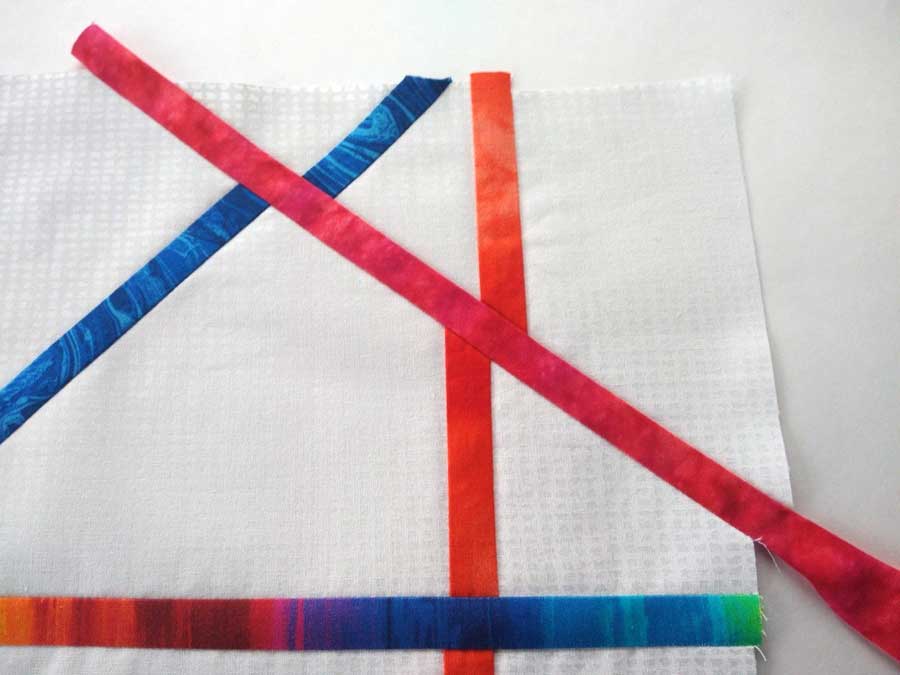

With right sides together and raw edges matching, sew one side of an inset strip to one side of the previously made cut. Press the seam allowances toward the inset.

Matching the second side to the adjacent base section raw edges, sew the remaining inset edge to the opposite side of the cut. Press the seam allowances toward the inset. Trim the excess inset length.

Lay the pieced fabric right side up on your cutting mat. Decide on the angle of your next cut and slice it apart again. The second inset can be at any angle and can bisect the first inset or not, depending on the desired effect.

Repeat steps 1-3 to complete the second inset.

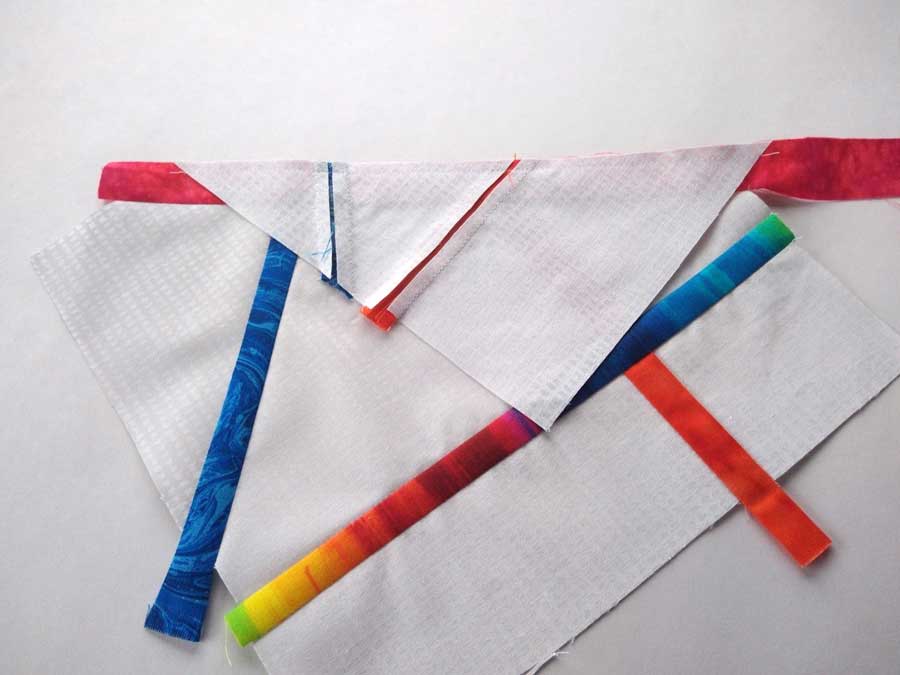

Continue in the same manner, slicing, insetting, and pressing until you have the desired look. Three to five insets per piece is an attractive addition. Note that the edges of the base fabric will not be even once strips have been inserted.

Tip: When you slice through an inset and reassemble the pieces, the adjacent inset sections may or may not align, depending on how you position the second section. If you choose to offset them, do so enough that the alignment looks purposeful and not as though it’s just slippage that caused it.

Once the base is complete, press it flat, and trim to the size needed, including seam allowances for further construction. If you’re making a small project or using the pieced section in a garment, cut out the pattern piece(s) from the completed section of fabric.

Beyond the Basics

- This technique can be used on almost any woven or non-woven fabric—think lightweight leather, denim, linen, silk, etc. It can work on knits as well if you stabilize the base fabric with fusible interfacing first to avoid stretching.

- For easier handling, especially on loosely woven fabrics, use spray starch or another pressing aid on the base fabric before starting the piecing to help stabilize bias-cut seams.

- The base fabric can be solid or print and so can the insets, so mix and match for fun.

- The inset pieces can be multiple colors or a single color, depending on the desired look.

- Use the new shapes created by the insets as a guide to quilt the fabric to fleece, foam or batting, depending on the project you’re making. For garments, pre-shrunk flannel backing adds a light touch without adding warmth.

- A single square is ideal as an inset in a jacket back, or turn under the edges and make it an appliqué. Add some piping around the edge to frame the featured section.

~Linda Griepentrog

Linda is the owner of G Wiz Creative Services and she does writing, editing and designing for companies in the sewing, crafting and quilting industries. In addition, she escorts fabric shopping tours to Hong Kong. She lives at the Oregon Coast with her husband Keith, and two dogs, Yohnuh and Abby. Contact her at gwizdesigns@aol.com.

Llamas, part of the camel family, are typically found in South America. Their fine undercoat is typically used for garments, while the courser outer hairs are more commonly used in rugs, wall hangings, and ropes. Llama fiber is normally available in white, black, grey, brown as well as reddish-brown colors.

Llamas, part of the camel family, are typically found in South America. Their fine undercoat is typically used for garments, while the courser outer hairs are more commonly used in rugs, wall hangings, and ropes. Llama fiber is normally available in white, black, grey, brown as well as reddish-brown colors. of Mongolia give the softest of camel hairs. China, Afghanistan, and Iran produce the most camel fibers in the world. Although most camel hair is left as its natural tone of golden tan, the hair can be dyed and accepts dye in the same way as wool fibers. Camel hair may be blended to create fabrics suitable for coats, outer sweaters, and underwear.

of Mongolia give the softest of camel hairs. China, Afghanistan, and Iran produce the most camel fibers in the world. Although most camel hair is left as its natural tone of golden tan, the hair can be dyed and accepts dye in the same way as wool fibers. Camel hair may be blended to create fabrics suitable for coats, outer sweaters, and underwear. Yaks are largely found in the Himalayas in India and Tibet. The hair of the yak is very useful in the production of warm clothes, mats, and sacks due to its warmth and strength. Yak fiber wool has been used by nomads in the Trans-Himalayan region for over a thousand years to make clothing, tents, ropes, and blankets. More recently, the fiber started being used in the garment industry to produce premium-priced clothing and accessories

Yaks are largely found in the Himalayas in India and Tibet. The hair of the yak is very useful in the production of warm clothes, mats, and sacks due to its warmth and strength. Yak fiber wool has been used by nomads in the Trans-Himalayan region for over a thousand years to make clothing, tents, ropes, and blankets. More recently, the fiber started being used in the garment industry to produce premium-priced clothing and accessories Brushtail possums are harvested under permit, and their soft pelts are plucked, shipped, spun and knitted into high-quality Australian apparel. There are tight regulatory controls over the harvest to ensure the possums were harvested correctly. It is commonly combined with other fibers, frequently Merino wool. When used to create Possum Merino knitwear, the combination of possum in the fabric leads to very lightweight garments. According to some sources, possum fur is 8% warmer and 14% lighter than wool.

Brushtail possums are harvested under permit, and their soft pelts are plucked, shipped, spun and knitted into high-quality Australian apparel. There are tight regulatory controls over the harvest to ensure the possums were harvested correctly. It is commonly combined with other fibers, frequently Merino wool. When used to create Possum Merino knitwear, the combination of possum in the fabric leads to very lightweight garments. According to some sources, possum fur is 8% warmer and 14% lighter than wool.

Not your typical marijuana plant, hemp can now be legally grown (within very specific restrictions) throughout the US. A more familiar use of this plant is as a source of CBD oil. And while it only captures a small portion of the textile market — less than 1% — it is also used to make fabric.

Not your typical marijuana plant, hemp can now be legally grown (within very specific restrictions) throughout the US. A more familiar use of this plant is as a source of CBD oil. And while it only captures a small portion of the textile market — less than 1% — it is also used to make fabric. It all starts with Mycelium; the fungus mushrooms are made of. When harnessed as a technology, it can be used to create everything from a plant-based steak to fabric. The cells are grown on beds of agricultural waste and the byproducts are compressed into an interconnected 3D network. Finally, it is tanned and dyed to create a product that resembles leather.

It all starts with Mycelium; the fungus mushrooms are made of. When harnessed as a technology, it can be used to create everything from a plant-based steak to fabric. The cells are grown on beds of agricultural waste and the byproducts are compressed into an interconnected 3D network. Finally, it is tanned and dyed to create a product that resembles leather. Fabrics are formed from a silk-like cellulose yarn made from citrus waste that can blend with other materials. When used in its purest form, the resulting 100% citrus textile features a soft and silky hand-feel, lightweight, and can be opaque or shiny.

Fabrics are formed from a silk-like cellulose yarn made from citrus waste that can blend with other materials. When used in its purest form, the resulting 100% citrus textile features a soft and silky hand-feel, lightweight, and can be opaque or shiny. While it may sound cutting-edge to create fabric from a banana plant, it was actually back in the 13th century when banana fiber cloth was first introduced in Japan. It comes from leave sheaths around the stem of the plant of abacá, a species of banana. The length of the fibers can be more than 3 meters long. Currently, it is being increasingly used in the manufacturing of garments, household textiles and upholstery thanks to innovations in the process of this fiber.

While it may sound cutting-edge to create fabric from a banana plant, it was actually back in the 13th century when banana fiber cloth was first introduced in Japan. It comes from leave sheaths around the stem of the plant of abacá, a species of banana. The length of the fibers can be more than 3 meters long. Currently, it is being increasingly used in the manufacturing of garments, household textiles and upholstery thanks to innovations in the process of this fiber. Often referred to as ‘pineapple leather,’ Piñatex® manufactures this material from the leaves of the pineapple, which are traditionally discarded or burned. There are several variations of the textile, with new developments for naturally dyed and 100% natural versions without the synthetic coating sometimes used to weatherproof the leather.

Often referred to as ‘pineapple leather,’ Piñatex® manufactures this material from the leaves of the pineapple, which are traditionally discarded or burned. There are several variations of the textile, with new developments for naturally dyed and 100% natural versions without the synthetic coating sometimes used to weatherproof the leather. “Wine leather” or “grape leather” transforms grape skins, seeds and stalks discarded during wine production from waste into a vegetal leather. And since 26B liters of wine are produced worldwide every year, the potential here is noteworthy.

“Wine leather” or “grape leather” transforms grape skins, seeds and stalks discarded during wine production from waste into a vegetal leather. And since 26B liters of wine are produced worldwide every year, the potential here is noteworthy.